In a desperate attempt to get my students to think about heavy philosophical issues last semester, I assigned my Freshman Comp I class a brief excerpt from Walker Percy's The Thanatos Syndrome. In it, Bob Comeaux admits to Dr. Tom More that his organization has placed a chemical into the water supply at and around Angola Prison, and that

One: The admissions to Angola for violent crime from the treatment area have declined seventy-two percent since Blue Boy began . . . Two: The incidence of murder, knifings, and homosexual rape in Angola, which is of course in the treatment area, has--declined--to--zero . . . We're treating cortical neurones by a water-soluble additive, just as we treated dental enamel by fluoride in the water fifty years ago--without the permission or knowledge of the treated . . . The hypothesis is that at least a segment of the human neocortex and of consciousness itself is not only an aberration of evolution but is also the scourge and curse of life on this earth, the source of wars, insanities, perversions--in short, those very pathologies which are peculiar to Homo sapiens.More feels instinctually that there's something evil and sinister in Comeaux's plan, and while he cannot articulate a logical argument against it, he does his best to stop Blue Boy from getting into the water supply of the rest of New Orleans.

This puts him a step ahead of my children, not one of whom had any objection to a plan like Comeaux's. All of them would be perfectly fine with adding such a chemical to prison water supplies (after all, prisoners are sub-human anyway), and only a few of them had vague reservations about it hitting the populace at large.

I was horrified, of course, and so I decided to try again. This semester, my kids read Don DeLillo's White Noise, a major plot point of which is the distribution of a drug called Dylar, which will ostensibily allow mankind to overcome its fear of death:

It's not just a powerful tranquilizer. The drug specifically interacts with neurotransmitters in the brain that are related to the fear of death. Every emotion or sensation has its own neurotransmitters. Mr. Gray found fear of death and then went to work on finding the chemicals that would induce the brain to make its own inhibitors.This proposition would perhaps not be so sinister if DeLillo hadn't already cued us to think that there's something about being human that makes us fear death. He speaks much earlier in the novel of "the irony of human existence, that we are the highest form of life on earth and yet ineffably sad because we know what no other animal knows, that we must die." To remove our fear and knowledge of our mortality is to make us somehow less than human. To know you're going to die is to know you're alive and to realize that means something.

The students responded much more negatively to Dylar; only a few of them said they would take it, although they couldn't really explain why not. A bunch of them used the old chestnut that "awareness of death makes life more precious," but as the protagonist of White Noise says, How precious can thirty years of fear and anxiety be?

What interests me more is that, when I asked them what the difference was between Dylar and anti-anxiety-disorder medications, they said, "not a lot." I have students--perhaps not the majority, but a lot of them--who believe that it's wrong or weak or sinister to take mood-stabilizing drugs. I had to tiptoe gingerly around the issue to some extent; I felt strange outright asking if anyone took them. But a few students volunteered that information and talked openly about their experiences with Adderall and Prozac, the way they worked for them and the way they resented having to take them to be "normal."

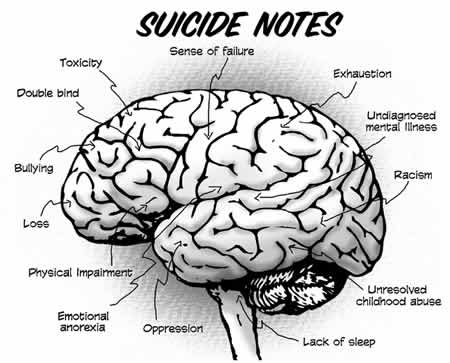

In a way, I sympathize with the students who fear and distrust pharmopsychology. Over Christmas break, I read David Healy's Let Them Eat Prozac, a disturbing history of Selective Seratonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs). The pharmaceutical industry, according to Healy, pushed these drugs even when it might not have been such a great idea, and even today most patients with mild depression are unaware that Prozac can increase their risk of suicide (in addition to completely flattening them out or sending them into what's called a "mixed episode," a combination of mania and depression that is, as far as I know, the most dangerous psychiatric state there is).

And then there's the issue of social phobia disorder, a supposed "mental illness" that Christopher Lane alleges was invented wholesale by the pharmapsychology industry in order to push medication. Shyness--a condition that's more or less benign and that's existed throughout human history--became illness. Have trouble stating my opinion in my class? Take this pill. Or, as Bill Mallonee, ever insightful, puts it,

When a need is nonexistent, you've got to create desireThat lyric sounds like something both Percy and DeLillo could get behind, this conflation of soft science with consumerism and sexual misethics.

Eastern Europe is the most likely buyer

They've been dying for it, crying for it, ever since the Wall

For syringes, porn, designer drugs, orgasms, and shopping malls

Meanwhile, This article claims that scientists are nowhere near understanding how the human brain works and that it's irresponsible at best to toss medication at an organ we don't understand. Psychiatry is a soft science masquerading as a hard one.

I've got a personal stake in this debate. A year and a half ago, I was diagnosed with cyclothymia, a "low-level" form of bipolar disorder. (I hesitate to use the term "low-level" because it's just as dangerous as full-scale bipolar--I just shift poles more quickly.) The suicide rate for unmedicated bipolar patients is one in three. My psychiatrist told me I was doing well not to have killed myself--and I complicated it.

The treatment I was given was Lamictal, an anti-seizure medication that somehow treats bipolar disorder--particularly that type of it that features depression more heavily than mania. Lamictal is not really comparable to SSRIs--it has few side effects. But there's something disturbing to me about the fact that I have a mental illness that psychiatrists cannot explain and that I take a medication that they also cannot explain. Like my students, I resent having to buy and take medication to get along in the world. My therapist told me to think of it like a diabetic who has to take insulin--the party line is that "chemical imbalance" stuff--but no one can tell me what chemical I naturally lack and need to have made up. I have by necessity an almost religious devotion to Lamictal, a blind faith in the pharmapsychology industry.

And yet I've been set free. I don't have depressive or manic episodes anymore, and I can function well in day-to-day life. My faith is rewarded, at least until that point in time when my body grows adjusted to Lamictal and I have to take another crapshoot to find another medication to make myself functional.

I'm afraid these are questions without easy answers; it's not as simple as my students want it to be (or as the pharmapsychology industry wants it to be, for that matter). I feel that in terms of psychiatry, we're still in the Dark Ages, applying leeches and mercury until we find something that we can explain. Doctors, as Hippocrates and Foucault suggest, are the new priesthood, and the rest of us are lighting tapers and dropping coins in the collection plate.

2 comments:

Thanks for this entry. The explanations are helpful. I've been meaning to read that DeLillo book for a while, so I'll have to bump it ahead on the list.

I think those types of stories are fascinating. "Harrison Bergeron" is a great short story that takes it in a direction that students would probably love to comment on...I'm planning to use it for a Comp I class this summer. The novel Terrarium also sparks a lot of thought along this vein. And then, of course, there's A Clockwork Orange, which features a controversy about different endings having to be published, and that takes this all to another level. Of course, all the stories I just mentioned take place in dystopian or anti-utopian worlds, whereas at least the Percy book appears to be more "realistic."

Thanks for the comment (and your frequent plugs on Facebook). I am hoping more people will comment on this post--it's my favorite so far.

I'd characterize the Percy and DeLillo books as "pre-dystopian"--they're the link, if there is one, from the world we live in to Huxley's "Brave New World." I'm not sure if the authors would agree--I suspect DeLillo in particular would say that the world we live in IS pre-dystopian--but I'm more optimistic than they are.

Post a Comment